The Apartheid Wall, also known as the Israeli West Bank Wall, extends roughly 708 km, or 440 miles, with 85% of the wall extending well beyond the Green Line—the pre-1967 armistice line demarcating Israel and Palestine. The Wall effectively destroys geographical and spatial continuity between Palestinian towns, turning what remains of Palestinian territories into Bantustans.

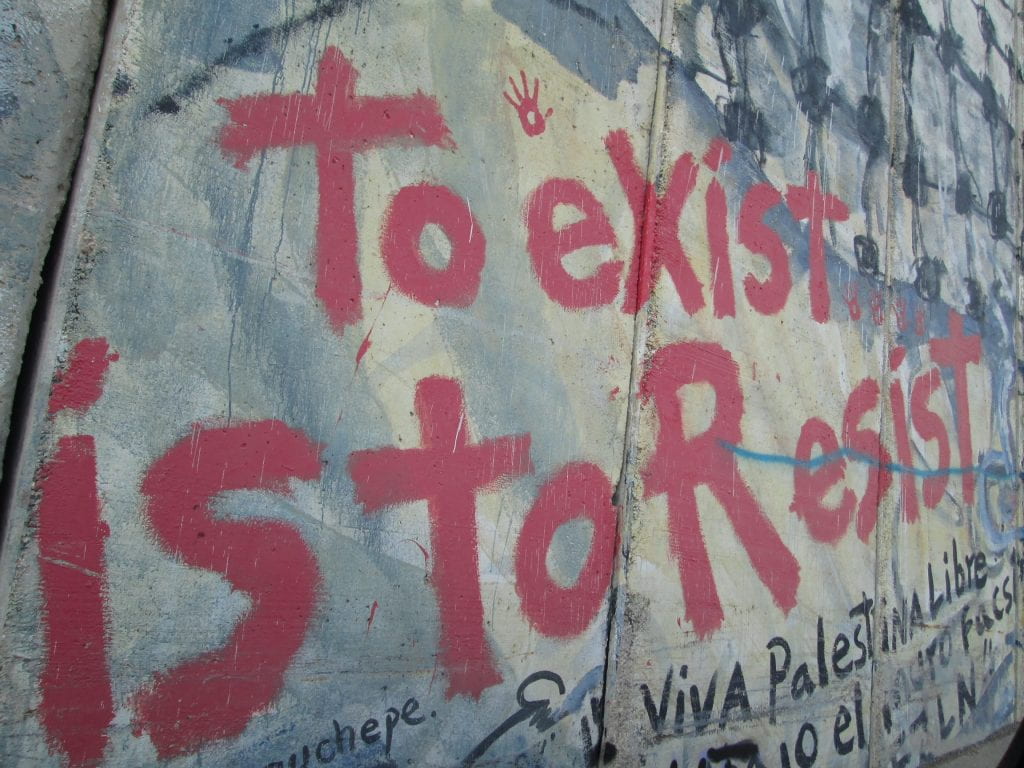

When the banalities of every-day life are invaded by an oppressive regime, local forms of resistance form to combat existing power dynamics. Given the domination Palestinian’s face vis-à-vis Israeli apartheid, sumud, or ‘stead-fastness,’ has emerged as a cultural expression of this resistance, often capturing the very same mundanities of day-to-day life, and breathing new, antagonistic life into them. In general terms, sumud embodies the spirit of opposition, maintaining that something as ‘simple’ as refusing to leave the land of Palestine behind is galvanized with unique socio-political force. While these acts can take on many different forms, street art—including graffiti—plays an overlooked role in challenging the apartheid conditions within the West Bank of Palestine, and is often recognized by local Palestinians and the diaspora of this art as sumud.

The art found inside (i.e., on the Palestinian side) of the Apartheid Wall illustrates a contested space of meaning, and a powerful, public practice for reclaiming contested space. These images and texts represent connections and communications with a global and transnational community, the surmounting of imposed isolation, and a narrative challenge to the dominant Israeli discourse surrounding the wall and the ‘occupation.’ This practice was prosaically referred to as the “un-walling of the wall” by Israeli architect Eyal Weizman.

The architecture within Israeli society serve as a means for perpetuating ‘facts on the ground’ and forms of control. To quote the afore-mentioned architect Eyal Weizman and his co-author Rafi Segal:

“The mundane elements of planning and architecture have been conscripted as tactical tools in Israel’s state strategy, which has sought to further national and geopolitical objectives in the organization of space and redistribution of its population. The landscape has become the battlefield on which power and state control confront both subversive and direct resistance” (A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture, 2003, p.19).

The significance of physical (and imagined) space, as well as the demographics of the population that exists within it, are vital for the Jewish and democratic state. The acquisition of land without its inhabitants is a staple of settler colonialism. This entails the militarization of civilians and their professions as vanguard forces to both claim space and to justify further militarization in defense of these ‘civilian’ outposts. Since the settlers and occupational forces comprise such an integral force of Israeli state building, the role of architecture, including the Apartheid Wall, in these acts of segregation is paramount.

The Wall demonstrates the dominance of one side and perspective over the other, as the disenfranchised are subjected to acceptance of the ‘rules’ and standards: porous and impermanent, for the Israelis, yet permanent and concrete for the Palestinians. The duality of the Wall continues when we consider tactics of surveillance and state observation, where the colonized population is simultaneously rendered invisible to the colonizers, despite their being incessantly monitored. The carceral impressions here are intentional, and it is within this context of control that we must perceive the street art found upon the Wall itself.

The use of graffiti challenges, from a Palestinian perspective, the intended political and structural consequences of the Apartheid Wall, emancipating a population from social control, censorship, and isolation through culturally significant messages and imagery. Graffiti is a means to redefining an overtly oppressive space. It contests perceptions and narratives—creatively un-walling the Wall. This is accomplished via the transformative effect street art has over a physical space, inverting the established realities of prison-like walls into message-boards and forums calling for liberation and democratic engagement. Indeed, much of the artwork has explicitly served to unify Palestinians

The volume of transnational travelers through Bethlehem, and the concentration of graffiti around this city results in a globalization of the graffiti. Using the internet, images of graffiti enter a global space, simultaneously redefining the public domain and reinterpreting the meanings of the graffiti themselves. These engagements allow for new, global networks and forms of solidarity to emerge, although they may also pose potential distortions or a de-localization of the Palestinian struggle.

Within Palestine, graffiti has been utilized politically and socially since at least the first Intifada, or Uprising, in 1987. Not only was it used for civic engagement to encourage resistance to the occupation, it also directly opposed Israeli control. As an alternative form of media and communication, graffiti forged a counter-narrative to the hegemonic U.S./Israeli perspective, and directly confronted Israeli attempts at censorship, community isolation, and political suffocation. “By using the wall as a canvas and bulletin board, as well as a site of resistance, Palestinians have found ways in which to establish agency against the wall—to ‘use’ it:”

“The fact of the graffiti, as well as the content of the graffiti, sometimes expressing solidarity, sometimes linking the wall and the occupation to the US (a reference to the US’ abundant foreign aid to Israel) both indicate that the act of producing graffiti on the wall is an act which inscribes a new meaning into the wall…It becomes both a thing and a place where people and ideas meet in opposition to the wall and to the occupation” (Toenjes “This Wall Speaks: Graffiti and Transnational Networks in Palestine.” Jerusalem Quarterly Issue 61: 55-68)

Perhaps the earliest example of Palestinian art-turned-graffiti comes in the form of Handala, created by Naji al-Ali, a political cartoonist. Handala’s age of 10 years old represents the artists’ age when he was forced from his home during the Nakba, or ‘catastrophe.’ His hands are “always clasped behind his back as a sign of rejection at a time when solutions are presented to us the American way,” in the words of the artist, and his back is always to the viewer as recognition of the denied right of return for Palestinians (Gould 2014: 10-11). Naji al-Ali was assassinated in 1987 for his controversial artistic renderings, a testament to the power and potential of art.

It is this seemingly mundane characteristic of graffiti that belies its impact. We can all understand how major social and political struggles do not manifest change in a moment, but through successive moments that are built upon one another. Such change requires tenacity and optimism in order to sustain the movement. Much of the street art found in the West Bank is a means of unification, an alternative form of media, or message-board, announcing strikes, collective actions, and newsworthy events, as well as serving as a massive memorial for all those lost to Israeli oppression. For Palestinians living in the shadow of the Apartheid Wall, images such as al-Ali’s and countless others provide them with hope and a sense of solidarity. For many, they encourage resilience to see them through one more day, one day at a time.

Citations:

- Gould, Rebecca. 2014. “The Materiality of Resistance: Israel’s Apartheid Wall in an Age of Globalization.” Social Text 118 Vol. 32, (No. 1): 1-21.

- Toenjes, Ashley. 2015. “This Wall Speaks: Graffiti and Transnational Networks in Palestine.” Jerusalem Quarterly Issue 61: 55-68.

- Weizman, Eyal. 2007, 2012. Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation. New York, NY: Verso.

Further Reading:

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326607902_Oshinski_thesis_2018

- Pappe, Ilan. 2006. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. London, England: Oneworld Publications.

- Said, Edward W. 1994. The Politics of Dispossession: The Struggle for Palestinian Self-Determination, 1969-1994. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Segal, Rafi and Eyal Weizman, eds. 2003. A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture. New York, NY: Verso.

- Zureik, Elia. 2016. Israel’s Colonial Project in Palestine: Brutal Pursuit. New York, NY: Routledge.

We are all aware that significant social and political movements bring about change gradually through incremental changes rather than all at once.