Background

The relationship between states and their Muslim citizens has a long and complex history within Central Asia. As a majority Muslim region, Islamic identity plays an important role in the everyday life of millions. Recognizing this, Central Asian governments often struggle between two paths: adopting Islam for political gain or repressing it for regime security. Unfortunately, governments often resort to the latter. Although the consequences of such policies have been debated for decades, the export of Central Asians to ISIS in Syria and Afghanistan, and recent high-casualty terrorist attacks committed by them have sparked renewed interest in religious repression, as scholars seek to identify or dispel its role in the radicalization of thousands. To assess the security implications of religious repression the religious identity, tools of religious repression, and factors that lead to the radicalization of Central Asians must be addressed, as the neglect of any of these areas fails to completely capture the nature of religious repression, and the corresponding radicalization in Central Asia.

Religious Identity in Central Asia

The arrival of Islam predates the creation of modern Central Asian cultures by centuries. But its adoption largely coincided with the traditions of the region.[1] Once modern cultures did begin to develop, they adopted Islam over varying periods of time, and in ways largely based on where and how they lived. For the more sedentary communities in present Uzbekistan and Tajikistan Islam developed much earlier, which served as a foundation for the evolution of Tajik and Uzbek identity. Historic mosques and madrassas that still stand today became centers of Islamic jurisprudence for centuries, which aided the development of a rich Islamic heritage.[2] Inversely, the Kyrgyz and Kazakh could not develop formal religious institutions due to their nomadic lifestyle. Instead, Islam was adopted slowly, and in a way that better fit nomadic culture, often being mixed with the spiritual traditions. Traditional shamanistic practices like Tengrism were Islamized, leading to a “folk Islam” that was largely informed by existing traditions. After the Russian conquest of Central Asia, Islam continued to spread and strengthen its footprint in the region into the Tsarist period, as scriptural Islam finally penetrated nomadic communities.[3] Unfortunately, the Soviet Union would impose drastic changes on its Muslim population, many of which have modern repercussions.

For nearly the entirety of the Soviet experiment, any overt expression of religion in Central Asia, especially Islam, was prohibited outside official channels. Mosques and madrassas were closed, and historical Islamic names took on patronymic endings. Islam became family oriented and unorthodox, as Central Asia was cut off from the wider world of Islamic scholarship and practice.[4] Local and informal practices transferred to the post-Soviet period, where, although identifying as Muslim, Islam is considered less dogmatic in Central Asia than in other majority Muslim nations.[5] Still, as the region’s main religion, and with a population that is more than 90% Muslim, Islam continues to have profound impacts on Central Asian society. Understanding its impact, and having to reckon with rapid re-Islamization following independence, Central Asian governments have employed a diverse range of strategies when it comes to Islam and the state.

Since independence Central Asian states have been governed by former communist officials with very few exceptions. Due to their Soviet influences and desire for regime security these governments were, and continue to be, reluctant to associate themselves too closely with Islam. At times it can be used as a tool for national unity or political expedience. But when unity among Muslims excludes the state, then that unity becomes a threat to the state. Regimes have historically sought to prevent this at all costs, as it undermines the hyper-nationalist, secular rhetoric and ideals that governments espouse in the pursuit of ethnic national identity.[6] They routinely use state institutions to repress this perceived threat.

Tools of Religious Repression

Religious repression in Central Asia is not monolithic. In the wake of rapid Islamic resurgence post-independence, and a civil war largely fought on religious grounds, Central Asian governments had to make decisions based not only on regime goals, but also on national characteristics. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, for example, have historically had much softer restrictions when compared to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. This can be attributed to a number of factors, chief among them the fact that these countries have historically weaker ties to the religion than their neighbors, which results in a less politically threatening Muslim community. In addition, the dominance of the politically useful Hanafi school, a lack of institutional capacity to effectively repress, and confessionally and ethnically diverse populations relative to their neighbors make heavy-handed measures politically unwise, unfeasible, or unnecessary.[7] The governments of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan reckon with a different reality. With a historically more devout Muslim community, their governments have had to decide whether to court or repress a brand of Islam that is concerned with political and social change.[8] Unfortunately, these governments typically resort to repression.

The Rahmon regime of Tajikistan is arguably the region’s most repressive. The Tajikistani Civil War, in which pro-government forces clashed with Islamist groups for more than 5 years, casts a large shadow over the government’s perception of Islam. The regime has been reluctant to allow Islamic expression ever since in the hopes that it cannot again be used as a political unifier.[9] As a result, the degree to which Islam can be practiced is tightly controlled. The law places clear limits on how many mosques can be built in each population area, restricts prayer to certain locations, and has put such stringent requirements on Islamic education that there are virtually no madrassas left in Tajikistan.[10] Additionally, the government has closed Islamic businesses, forcibly shaved the beards of Muslim men, and restricted how Islam can be practiced and taught to minors through freedom of conscience laws. Put together, these regulations strongly limit the degree to which Tajik Muslims can practice their religion and who they can practice it with, greatly damaging the sense of community and creating a crisis of identity.[11] The regime also employs harsher tactics like arrests and state sanctioned violence.

The Tajikistani government routinely uses arrests, beatings, and other violent means of force to suppress Muslim organizations and populations. Especially prevalent in the traditional, ethnically diverse south, the use of force against Muslim groups is conducted under the guise of “counterterrorism”. In reality these measures are meant to repress organizations or individuals with political or societal goals that the regime finds threatening.[12] The Isma’ili Pamiri community, for example, recently suffered such an operation, where more than 200 individuals were arrested for “extremist” activity after participating in a protest.[13] These practices are in line with other generally authoritarian behavior of the country, where anti-regime activity of any kind is grounds for a lengthy prison sentence. Tajikistan is not alone in this behavior, as Uzbekistan has taken similar action on multiple occasions.

Although lacking the regime continuity of Tajikistan, the Karimov and Mirziyoyev regimes of Uzbekistan repressed Muslim communities in similar ways. Constitutionally defined as a secular state, various laws prohibit or restrict Islamic education and the creation of religious organizations, and some public displays of worship and belief are still considered “extremist”.[14] These laws are all broadly defined to disguise any overt persecution of a given belief as protection against extremism, especially when it comes to religious materials. The regime has also been highly restrictive of the religiously educated, confiscating passports of Imams and increasing the restrictions on who they can interact with.[15] Uzbekistan also has a penchant for heavy handed tactics against the Muslim populations it deems threatening. Thousands of Uzbek citizens have been imprisoned on dubious charges related to their religious expression. Of those detained, there have been numerous documented cases of ill-treatment and abuse.[16] It should be noted that Uzbekistan has made nominal progress on religious freedoms through the release of prisoners and relaxation of rules regarding religious dress, but this has not resulted in a loosening of restrictions writ large.

Radicalization and Its Causes

Religious repression is often argued to be a factor in radicalization. Central Asia, at first glance, seems to give credit to this argument, as approximately 4,000 Central Asian nationals migrated to join ISIS during its war with Syria.[17] Moreover, Central Asians, particularly from Tajikistan, are routinely implicated in terrorist plots, or uncovered as the ones behind successful attacks. The most recent examples of this are the Crocus City Hall attack of 2023, various foiled plots intended for Western Europe and the United States, and the overall rise of ISIS-K in Afghanistan, whose ranks are largely bolstered by Central Asians.[18] Central Asia itself has also fallen victim to extremist activity, but this has declined sharply since 2016. However, a closer examination raises questions about the role religious repression plays in Central Asian radicalization.

Scholars from a variety of academic disciplines have argued diverse factors lead to radicalization, including but not limited to economic hardship, social exclusion, and a host of psychological and structural factors that create grievances within an individual or community. Radical groups then capitalize on these grievances by providing opportunities for individuals to address injustices and inequalities.[19] Central Asian Muslims fall victim to a number of these factors, especially when it comes to the lack of economic opportunity. The religious repression hypothesis is further complicated by the fact that many Central Asians are radicalized abroad, and the relatively low numbers of Central Asian fighters compared to other Muslim nations.[20] Moreover, religious repression is just one of a host of actions regularly taken by Central Asian governments that lead to political, social, and economic isolation.[21] However, the presence of multiple factors does not negate the effect of one.

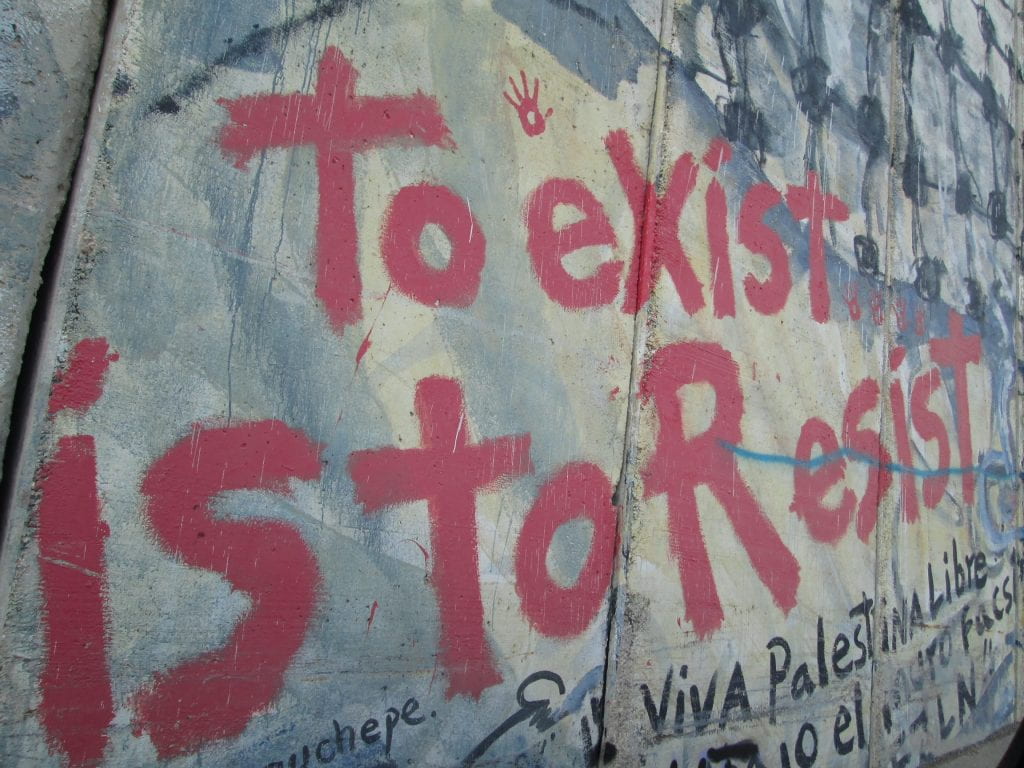

It is true that religious repression is not the sole cause of radicalization, and that the Central Asian terrorist threat has at times been sensationalized. But it is also true that many Muslim Central Asians possess powerful grievances based on generational inequality and repression. It is true that terrorist groups know about this reality, as they have taken large steps to recruit central Asians through multi-language propaganda campaigns. It is true that the location of radicalization is largely immaterial to the case of Central Asia, as the factors that put individuals at risk of radicalization are largely incurred domestically; social remittances likely make those domestic factors worse.[22] And it is true that once radicalized, Central Asians have gone on to conduct attacks around the globe.[23] Therefore, it is highly likely religious repression among Muslim populations that have been deprived of the religious freedom and dignity they desire is a large factor in the eventual radicalization of an individual. If this is true, then it carries implications for international security.

Security Implications

ISIS-K and other Islamist groups that recruit Central Asians possess a capacity for destruction well beyond their size. By shifting towards a strategy based on remote coordination, which is more well suited to their smaller numbers, they have been able to undertake high-profile terrorist attacks in Afghanistan, Russia, and Iran.[24] Multiple plots have been uncovered in Western Europe and the U.S., further underscoring the group’s international goals. If these groups are continuously able to draw from a Central Asian recruiting pool, the threat will persist. This is not to sensationalize the problem. ISIS-K and similar groups do not have the capacity to capture large amounts of territory and are not as large as the ISIS and al-Qaeda of old. However, given their demonstrated capabilities, the threat to international security cannot be discounted: every country is a potential target. In that light, it is critical the international community find a way forward.

The Way Forward

Although “over-the-horizon” measures eliminate terrorists, and words of condemnation look great on paper, they do not address the root cause of radicalization. As long as Central Asian governments continue to govern in a way that perpetuates historical grievances, Central Asians will continue to radicalize, and the threat will persist. Luckily, Central Asian Governments are not without options. Most importantly, aggrieved communities require a method of legitimate political expression. As Tajikistan up until 2015 showed, radicalization is less likely when unsatisfied communities can legally voice their opposition and desires.[25] By allowing these avenues to exist, governments take away a crucial recruiting tool for extremist organizations, as individuals can now voice their displeasure in ways that don’t require violence. Central Asian states should also soften social restrictions on religious expression. Like political repression, social repression of Islamic identity through dress, education, and worship restrictions is a large source of anger for Central Asian Muslims.

These are not the only improvements Central Asian governments can make, and it is not the only problem they are facing. Just like religious issues, the lack of economic opportunity is a large factor in radicalization. Central Asia likely cannot reform itself alone, as authoritarian governments have little incentive to alter the status quo: it has kept them in power for more than 30 years. Whether or not partner nations, particularly in the West, can convince or coerce Central Asian governments to change will be the defining factor. This does not mean “democracy promotion”. Multiple efforts over the past 2 decades have shown that to be a bad policy. Foreign policy practitioners should instead look to the most basic of international relations tools: carrots and sticks.

Authoritarian governments do not respond well to sticks. They would be even less effective in Central Asia, which could always turn to Russia or China to subvert them. Instead, Western governments should resort to carrots, by giving Central Asian governments something in return for their cooperation on human rights. As developing nations, Central Asian states are desperate for investment and development aid. Changing their policies towards Islam, and moreover, all religious expression, is a potential offering in exchange for it. These would be an exceptionally useful tool for the region, who largely suffer from agrarian, stagnant economies and security sectors lacking in capacity. This also has tangible benefits for the West, as cooperation creates new economic partnerships in a geo-politically contested region and addresses shared security challenges. Crucially, Western governments would do well to seek these changes now. Central Asia’s neighbors, namely China and Russia, have treated their Muslim populations similarly, and will not require any returns for their continued investment and aid.

Religious extremism has never been an issue of “if”, it has always been “when”. The post-ISIS complacency of the late 2010s and the emergence of Great Power Competition led many to treat the threat as if it were over, or as if it was too inconsequential to be given adequate attention. As recent years have shown, this could not have been further from the truth. This is not to say the West should resort to its War on Terror attitudes, as this would only exacerbate the issue. Instead, the West should lead a renewed push to address the root causes of radicalization, to further human rights and promote international security.

[1] S. Frederick Starr, Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Invasions to Tamerlane, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013.

[2] Lenz-Raymann, Kathrin. Securitization of Islam: A Vicious Circle: Counter-Terrorism and Freedom of Religion in Central Asia. transcript Verlag, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1fxgjp.

[3] Svante E. Cornell et al. “Religion and the Secular State in Kazakhstan” Silk Road Studies Program, 2018.

[4] Adeeb Khalid. “Islam After Communism: Religion and Politics in Central Asia”. University of California Press, 2007.

[5] Svante E. Cornell et al. “Religion and the Secular State in Kazakhstan” Silk Road Studies Program, 2018.

[6] Nartsiss Shukuralieva and Artur Lipiński. “Islamic Extremism and Terrorism in Central Asia: A Critical Analysis.” Central Asia and the Caucasus, 2021, 22: 106–17.

[7] Svante E. Cornell et al. “Religion and the Secular State in Kyrgyzstan” Silk Road Studies Program, 2020.

[8] Marlene Laruelle. “The Paradox of Uzbek Terror” Foreign Affairs, 2017.

[9] “UN Experts Urge Tajikistan to Leave Past Behind and Uphold Freedom of Religion and Belief”. United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner, 2023.

[10] Mollie Blum. “The Repression of Religious Freedom in Authoritarian Tajikistan” United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, 2023.

[11] Global Risk Insights. 2017. “Under the Radar: Tajikistan on Track to be the Next Afghanistan.” March 19.

[12] ‘Tajikistan: Events of 2023” Human Rights Watch, 2024.

[13] Blum 2023.

[14] “2025 Annual Report” United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, 2025.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Report on International Religious Freedom: Uzbekistan” U.S. State Department, 2023

[17] Edward Lemon. “Talking Up Terrorism in Central Asia” Wilson Center Kennan Institute, 2018.

[18] Noah Tucker and Edward Lemon. “A Hotbed or a Slow Painful Burn? Explaining Central Asia’s Role in Global Terrorism” July/August 2024, Volume 17, Issue 7.

[19] India Boland. “Expanding the Radicalization Framework: A Case Study of Tajik Migration to Russia.” Asian Perspective 46, 3, 2022.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Alessandro Frigerio. “Central Asian Authoritarianisms: Accounting for Differences and Regime Oscillations” The Oxford Handbook of Authoritarian Politics, 2024

[22] Boland 2022.

[23] Amir Jadoon et al. “From Tajikistan to Moscow: Mapping the Local and Transnational Threat of Islamic State Khorasan” CTC Sentinel, 2024

[24] Ibid

[25] Boland 2022.