October 29, 2021 “Spirits and Zombies in Japanese Buddhism and Western Christianity” with Prof. Rollie Lal

Our fears and imagination of afterlife beings are closely connected with the underlying religious beliefs of our communities. This is evident in common perceptions of ghosts, zombies, and vampires. Whereas some cultures place an emphasis on the spirit as the primary actor after death without the body, other cultures found that the body is the key after death, and the one to fear. To some extent, this hinges upon whether the body is even there. If the body is cremated, the zombie or vampire is a removed concept, and there would be few bodies to fear. Where burial is popular, the body becomes far more tangible, and people are able to envision possibilities of the walking dead.

Before the Middle Ages, in Japan there was the concept of the Hungry Ghosts—the undead corpse-eaters. The Japanese concept is quite similar to the western concept of the afterlife at this time. These Japanese ghosts had done terrible things in their life, for example greed, or violence. They are then punished with an unsatiable hunger that makes them eat horrible things such as excrement or dead bodies. In the painting of the Gaki Zoshi, from the 12th century, you can see the Hungry Ghost eating a dead body. Certain Gaki were even believed to eat live bodies, which would place them in the category of what we call zombies.

These Hungry Ghosts also indicated how physically difficult life was in Japan at the time. There was starvation, and people may have been forced to eat unfathomable things to stay alive.

In contrast, in the Christian tradition, the Bible makes very little reference to ghosts. Ghosts were not a part of the spiritual system, as the soul upon death was meant to go to heaven, hell, or in certain cases, purgatory. There was no reason for a soul to be wandering about the world haplessly. Interestingly, the soul in this system could also be punished physically. In hell, the soul could be burned, and in the painting “The Coronation of the Virgin” by Enguerrand Quarton you can see that the souls are also purified in purgatory by being burned. These souls are then very physical, similar to bodies. In these ancient times, the concept of the afterlife on the Japanese side and the Christian side are actually not so different. In either world view existed a painful afterlife where your ghost or soul could be tortured if you had misbehaved.

At that time, burial was common in both Japan and the Christian regions to dispose of the body. Japan has burial mounds very early on, and both Shintoism and Confucianism, burial was normal. And while the spirit has its place in the Christian tradition, so does the body upon death. In death, there is an important emphasis on physicality that contrasts sharply with the eastern traditions. The resurrection of Jesus into a body of flesh and blood is very much a critical element of Christian theology (Luke 24:39). It is also central in the Christian context that Jesus be accepted as not just a ghostly presence, but a physical one (1). Historically, the Catholic Church taught that the body and the soul ultimately will be reunited, and so the body has to be treated with respect and buried (2). This is a result of two ideas. First and foremost the belief in the resurrection led to the essential nature of burial.

The second reason was also influential– the fact that atheists who were denying the resurrection during the enlightenment were having cremations done as a form of protest against the church. This set up a situation where the church banned cremation (and protests against the church) as a way of emphasizing faith in the resurrection and clarifying who the rebels were. The Catholic Church ban on cremation for followers continued surprisingly until 1962 (3).

In Japan, cremation launched in the 8th century following the spread of Buddhism, with the cremation of a priest in 700 AD and Emperor Jito in 703 AD (4). According to Buddhist philosophy, the body is not permanent, and the process of cremation is purifying for the body and the spirit. Buddhist theology emphasizes that there should be no attachment to the body, and therefore after death, cremation of the body is not only accepted, but recommended. Nonetheless, some debate continued between Confucians who believed in burial and the Buddhist groups, but after the Meiji period, Japan settled upon cremation, as it was far more efficient in terms of use of land and allowing families to keep the remains of loved ones nearby to visit.

You can see that there is a fundamentally different perception of how the spirit and the body are connected. In Japan, the body is not necessary, and in fact you need to remove it to be pure. In the Catholic concept, the body needs to remain, or you are actually in some way denying God by denying the resurrection of Jesus.

In popular lore, some of the impact of these differences becomes clear in the appearance of the ghosts. In 11th century Japan, the novel The Tale of Genji has a philandering prince who makes many women jealous (5). So much so that the angry and jealous ghost of one of his lovers, Lady Rokujo, leaves her body while she is still living and kills the lady he loves (Aoi). The painting of the jealous Lady Rokujo shows the ethereal and beautiful depiction of the Japanese ghost. The Tale of Genji is steeped in Buddhist tradition.

The spirit is so powerful in the Japanese context that it can do double time—keep someone alive while wandering off and killing. In folklore, if someone dies violently or if the funeral rites weren’t performed, the spirit can return to the world after death until the conflict is resolved. These ghosts (yurei) are usually young women wearing white clothes that are traditional in Buddhist funerals, and long black hair.

For comparison, in the West we have the cultural influence of Shakespeare on the interpretation of the afterlife. In the 17th century, he brings in ghosts and witches. The painting by Henry Fusili of Shakespeare’s Macbeth you can see an armed head. In Shakespeare, there is a physical armed head which depicts a ghost that is telling him the future. The ghost is very physical in that it has a helmet, and it is also just a part of the body. A ghost could theoretically be the full representation of the person, but in this case Shakespeare is specific in identifying the ghost as a very tangible helmeted head upon the floor.

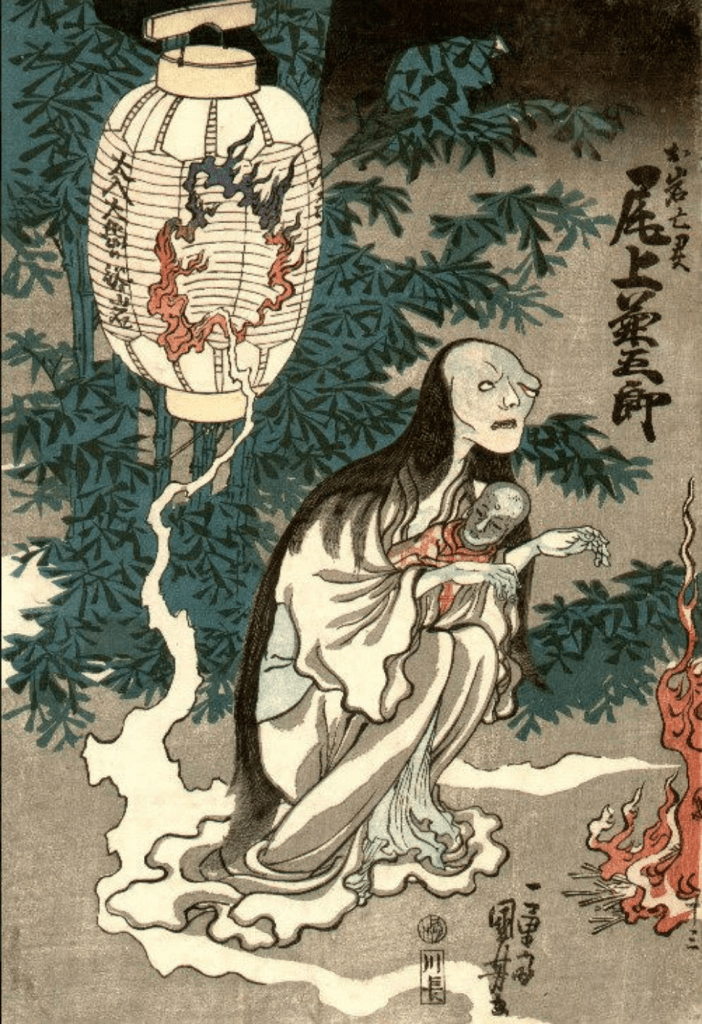

As we move forward, the divergence of how Christians in the West and Buddhists in Japan view the afterlife becomes apparent. The most famous ghost story from Japan that has set the stage ever since, is about Lady Oiwa, who shows up in Kabuki plays about 200 years ago. She is a lovely woman who is unfortunate enough to be married to a very evil man. He has fallen for another woman who he would like to marry, and the father of his lover is a doctor. The father/doctor sends medicine for Lady Oiwa, but it is in fact poison. She uses this poison unknowingly as medicine, causing her face to become completely disfigured. Her hair then falls out in clumps, and her eye droops—she becomes hideous. The painting of the Ghost of Oiwa shows this pathetically disfigured ghost.

Paintings of the ghost of Lady Oiwa portray her with the long black hair and long white robes that are reminiscent of Lady Rokujo (Tale of Genji). This becomes the established female ghost in Japan.

In the West, afterlife tales revolve much more around the dead body and its adventures after the burial. In recent years, a skeleton was excavated in Venice, Italy that exhibited signs of local beliefs surrounding the possibility of undead threats. During the Middle Ages and afterward, the existence of the Black Plague created problems with the normal dignified burial process. Whereas normally bodies could be buried and be undisturbed, during the plagues the number of bodies accumulated rapidly. This led to the need for mass graves, and the reopening of graves just months after burial to add more bodies. Apparently upon opening the graves on occasion, people witnessed blood or other liquids from deteriorating bodies exiting the mouth and into the burial shroud. This would appear as though the body was attempting to eat through the shroud and escape to spread disease (5). Fear of these attacking undead led to strange and extreme measures, such as the placing of a brick or stone in the mouth of the body in order to prevent it from eating through and escaping to attack the living.

In other regions, such as Bulgaria, archaeologists have discovered that people believed the plague corpses would rise as vampires and drink the blood and life of humans and livestock. To prevent these possible attacks, the locals pounded an iron of wooden stake through their chest and into the ground (6). This technique was hoped to keep the body in the grave.

The physical manifestation of the afterlife as undead bodies in Italy contrasts sharply with the ethereal and flowing ghost of Buddhist Japan.

Today we can see the manifestation of these differences in scare tactics of the popular Japanese movie Ringu and its American remake, The Ring. In Japanese Ringu, the ghost is a girl who has been killed by her father and thrown in a well, as she was evil. But her ghost nonetheless is clean, wearing a long white dress, and with long black tresses. Her character is clearly modeled upon the image of the ghost of Lady Oiwa, including the detail of the drooping eye (7). She is in many ways a sympathetic ghost, scary not because she is ugly, but because she has spiritual power. However, when the film was being remade in the US, director Gore Verbinski decided that this ghost image was not scary for US audiences. Americans do not find clean white ghosts to be terrifying. The ghost would need to become more familiar to the western concept of the afterlife. In the American version of The Ring, the girl is similarly clothed in a white dress with long black hair, but with a critical difference. She is filthy, her hair matted and dirty, and her face is monstrous (8). She came from the well, and has the physicality of having emerged from the earth.

Henry Fuseli, “Macbeth Consulting the Vision of the Armed Head”, 1793

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, “Onoe Kikugoro as the Ghost of Oiwa in Yotsuya Kaidan”, 1836

See Professor Lal’s accompanying slideshow here

See the complete lecture series on “Spirits, Zombies and Vampires Around the World” on our YouTube! Featured talks include: Japanese Buddhism and Western Christianity by Prof. Lal, Korean Zombies in Popular Film by Prof. Oh, and Chinese Female Ghosts in Folklore by Prof. Kang.

- Matthew James Ketchum, “Specters of Jesus: Ghosts, Gospels, and Resurrection in early Christianity,” Ph.D. Dissertation for Drew University, May 2015.

- Matthew 27:50-54 50 And when Jesus had cried out again in a loud voice, he gave up his spirit. 51 At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom. The earth shook, the rocks split 52 and the tombs broke open. The bodies of many holy people who had died were raised to life. 53 They came out of the tombs after Jesus’ resurrection and[a] went into the holy city and appeared to many people. 54 When the centurion and those with him who were guarding Jesus saw the earthquake and all that had happened, they were terrified, and exclaimed, “Surely he was the Son of God!”

- The Vatican (Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith), Instruction Ad resurgendum cum Christo Regarding the Burial of the Deceased and the Conservation of the Ashes in the Case of Cremation, March 2, 2016; https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20160815_ad-resurgendum-cum-christo_en.html

- Anna Hiatt, “The History of Cremation in Japan,” JSTOR Daily, September 9, 2015. https://daily.jstor.org/history-japan-cremation/

- Murasaki Shikibu, The Tale of Genji, trans. Suematsu Kencho (Tuttle Publishing, 2018). (originally published in 1008 CE).

- Daniel Flynn, “”Vampire” Unearthed in Venice Plague Grave,” March 12, 2009, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-italy-vampire/vampire-unearthed-in-venice-plague-grave-idUSTRE52B4RU20090312

- The Week, “Unearthed: Bulgarian ‘Vampire’ Skeletons,” January 8, 2015, https://theweek.com/articles/474918/unearthed-bulgarian-vampire-skeletons

- Valerie Wee, “Patriarchy and the Horror of the Monstrous Feminine: A Comparative Study of Ringu and The Ring,” Feminist Media Studies, 11(2), 2011.

- Matthew Ducca, “Lost in Translation: Regressive Femininity in American J-Horror Remakes,” City University of New York Thesis, 2015, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1926&context=gc_etds